Day in and day out across the country, local newsrooms report on their communities' good and bad news — even the most shocking crimes. But despite the increasing occurrences of mass shootings in the U.S., no newsroom can ever fully be prepared to tell the story of a community brought to its knees by the mass murder of children in their classrooms — a sacred place to learn, make friends, mature and grow, to feel safe and to be safe.

Nineteen children and two educators were denied that on May 24, 2022, when a single shooter opened fire at Robb Elementary in the small town of Uvalde, Texas.

The local paper, the Uvalde Leader-News (ULN), was presented with a profound challenge on that day and in the years since. Not only did they have the duty to inform the public about the tragedy, they felt it acutely themselves. Alexandria “Lexi” Rubio — the 10-year-old daughter of Crime Reporter Kimberly Mata-Rubio — was among the victims.

Their focus was even more difficult as state and national reporters descended on their small town, many looking to the local journalists for context and access. E&P was one of the thousands of phone calls fielded by the newsroom in that first week. We wanted to understand what it takes for a newsroom to manage a transformative, monumental story of this kind. We wanted to know what they needed. Mostly, we wanted them to know we shared in their sorrow.

The news community is relatively small — and getting smaller — and when we lose a member of our extended family, we grieve together.

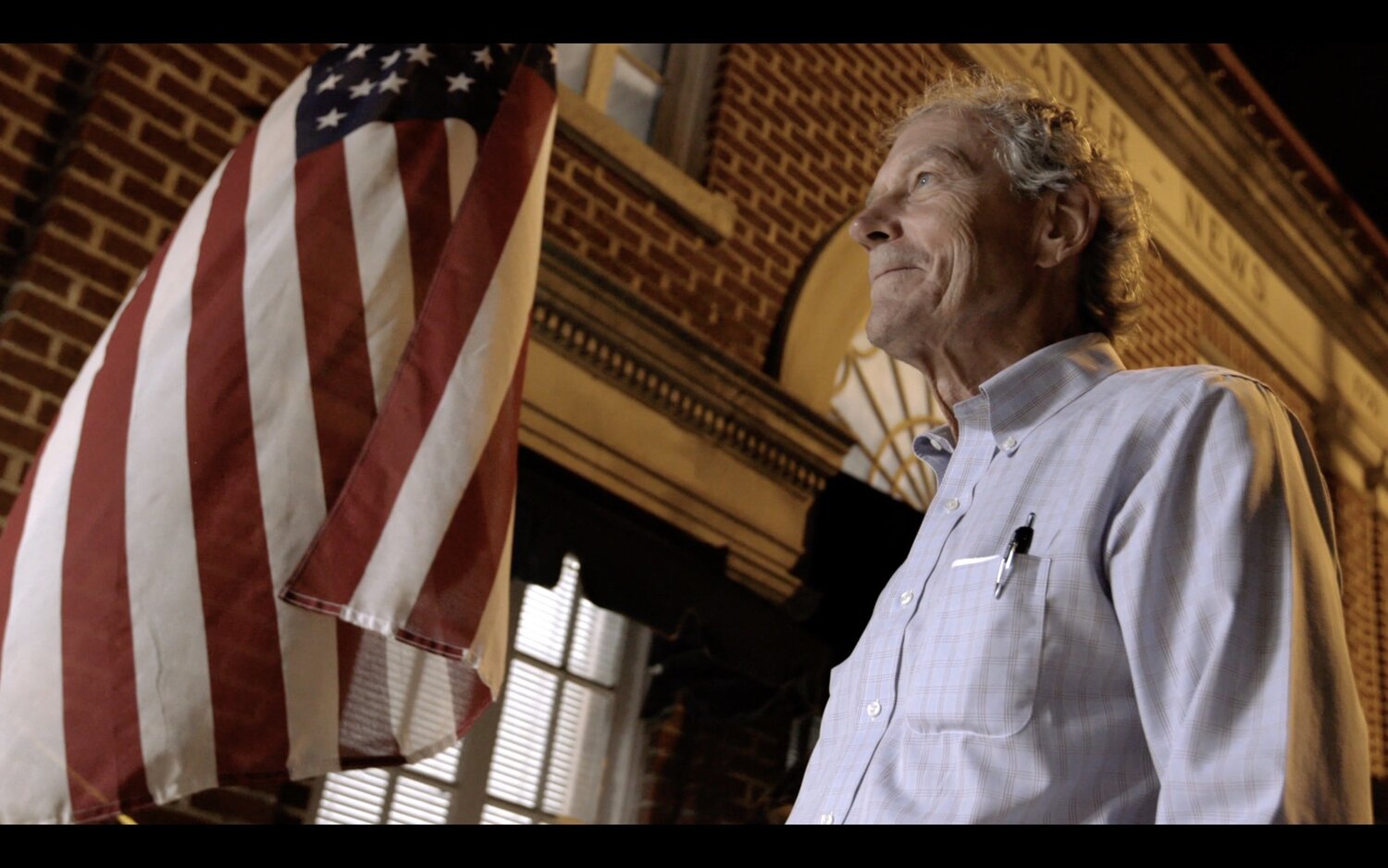

E&P was one of many news media outlets that took an interest in what their newsroom was experiencing. Owner-Publisher Craig Garnett was approached by ABC News about allowing a documentary film team into their lives. It wasn’t an easy decision to welcome them — an embedded field team that included Producers Andrew Fredericks and Megan Hundahl Streete — because journalists are not supposed to be the story and because their grief was so very raw. But they opened the doors to the newsroom and their lives for the documentary, “Print It Black.”

The film was awarded Best Documentary at the 2024 Dallas International Film Festival. It tells the story of a small town where 25% of the residents live below the poverty line and where racism and classism are on full display. It also tells the story of unimaginable grief and resilience. And it tells the story of a local newsroom.

In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, the community looked to the newspaper for an accurate account. However, they were dealing with so much incoming information, speculation and lack of access to officials that it felt like “haywire.” “We just took what we had — pieces we were able to nail down — and cobbled together the best stories we could,” Garnett said.

“We just dug in and cried, yelled and screamed and got what we could,” he added.

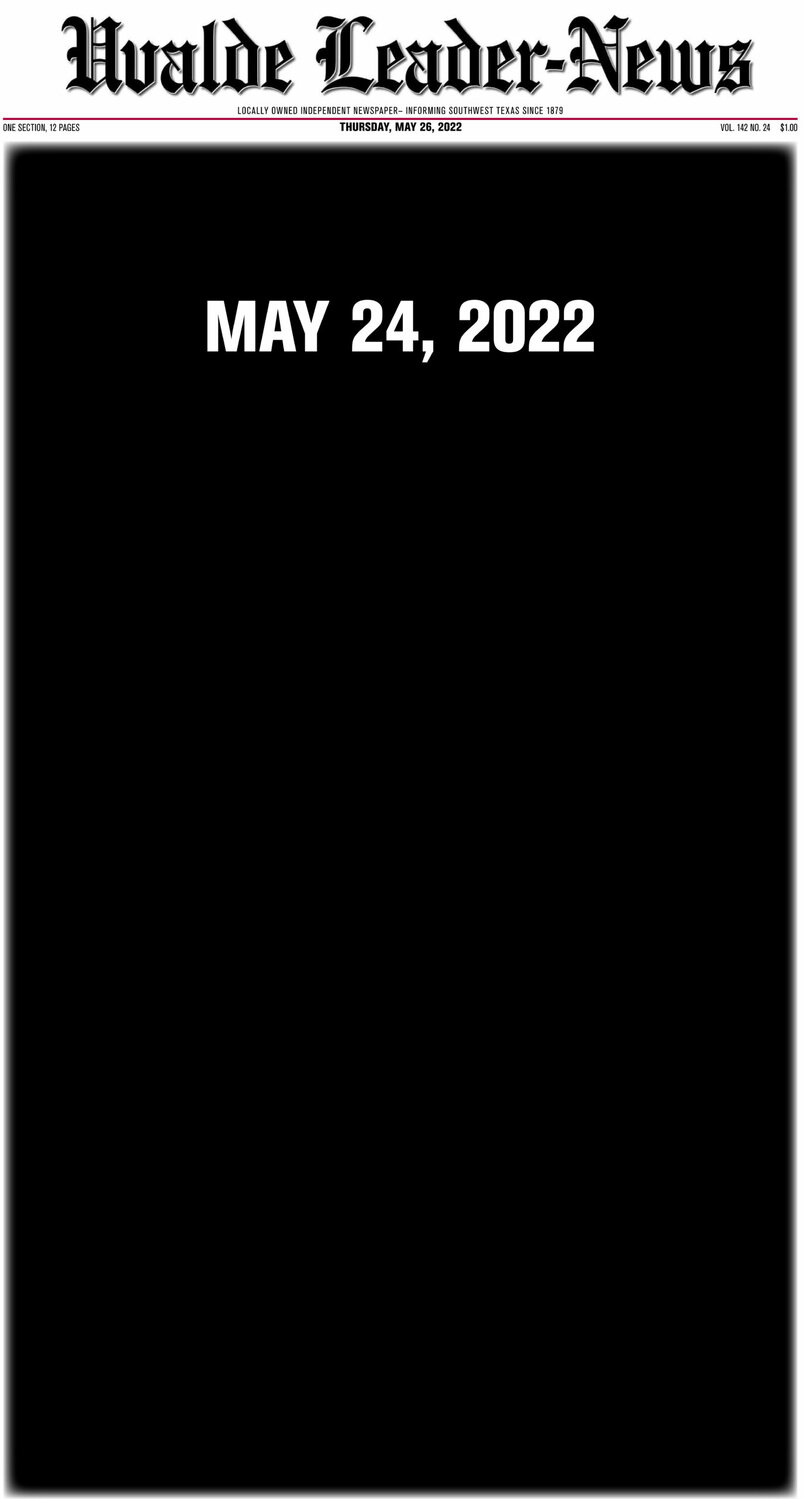

“Print It Black” refers to how the newsroom handled the following day’s 1A page. Reporters suggested a stark black cover page with just the date of the tragedy in striking white contrast. Garnett spoke in the documentary about being unsure that was the best way to lead into the next day’s storytelling. He pondered whether photos and a more traditional news headline might be best.

They ran the black page — a design decision that reflected the darkness of that day, the absence of light or words that make sense of the nonsensical.

It wasn’t the only difficult dilemma they considered. They also had to decide what pictures to publish in the paper and what video clips to share on their site. Of all the images they gathered that day, they chose fewer than 30 to publish and share.

“We were inundated with requests for images,” Garnett said. “We simply didn’t know how to create a licensing agreement — or even want to go through the process of asking for money, for it felt almost disrespectful to the children who died — to their families — to ask for money for our images. And that led us to say, ‘We’re going to release these images to the most qualified news outlets.’ Many still used them without our permission.”

The documentary captures the spirit of the newsroom — an all-hands-on-deck culture. There is a sense of a collective mission and whatever it takes to rise to it.

“I think part of it has to do with the size of our staff,” Garnett said.

“We've all just become accustomed to filling in for others when someone’s on vacation, ill or out with COVID. But I have never once heard these people push back on taking on more. And when the shooting happened, it was just more of the same,” he recalled. “It was, ‘We’re all going to lift each other up. We’re going to get through this.’”

Journalists are expected to be stoic, objective, steely.

“There were times when I think we probably lost some objectivity, angered by institutions that refused to divulge even the most basic information. … We weren’t always able to put aside our emotions,” Garnett reflected.

Of course, the story didn’t conclude in a week, a month or even more than two years later. A profound event of this kind has long-stretching tentacles that reach into the unforeseeable future.

There are teachable moments and accountability questions to consider. A mass shooting influences elections and local politics. There are the stories of how the community comes together to heal — or fractures, as was the case with Uvalde. For the newsroom, coverage continues. “We had two indictments the other day of police officers,” Garnett told E&P in late July 2024. “This story is like a boiling stream, turning over debris as things pop up.”

“There’s a segment of the community that does not like that,” Garnett said. “They want this traumatic visitor to pack up his suitcases and his tent and get the hell out of town.”

One of the many startling scenes in the film shows a vigil for the victims interrupted by an off-camera motorist who yells at the assembled crowd, “Move on!”

Garnett believes that the dark underbelly of racism and classism is why there was so much polarization in the community.

He’s written a book about it, “Uvalde’s Darkest Hour,” to be published in October by Texas A&M University Press.

“Robb Elementary was ‘the Mexican school’ back in the 50s. We got past that. We integrated, but on some levels, we didn’t. Hispanics were upwardly mobile, and that caused jealousy among some. … I think racism has been unwavering. We think it’s gone away, if you will, but this just ripped it open again,” Garnett said.

Politics at the national level haven’t helped. In fact, the political rhetoric has been an “accelerant” that “heats things up on both sides,” he observed.

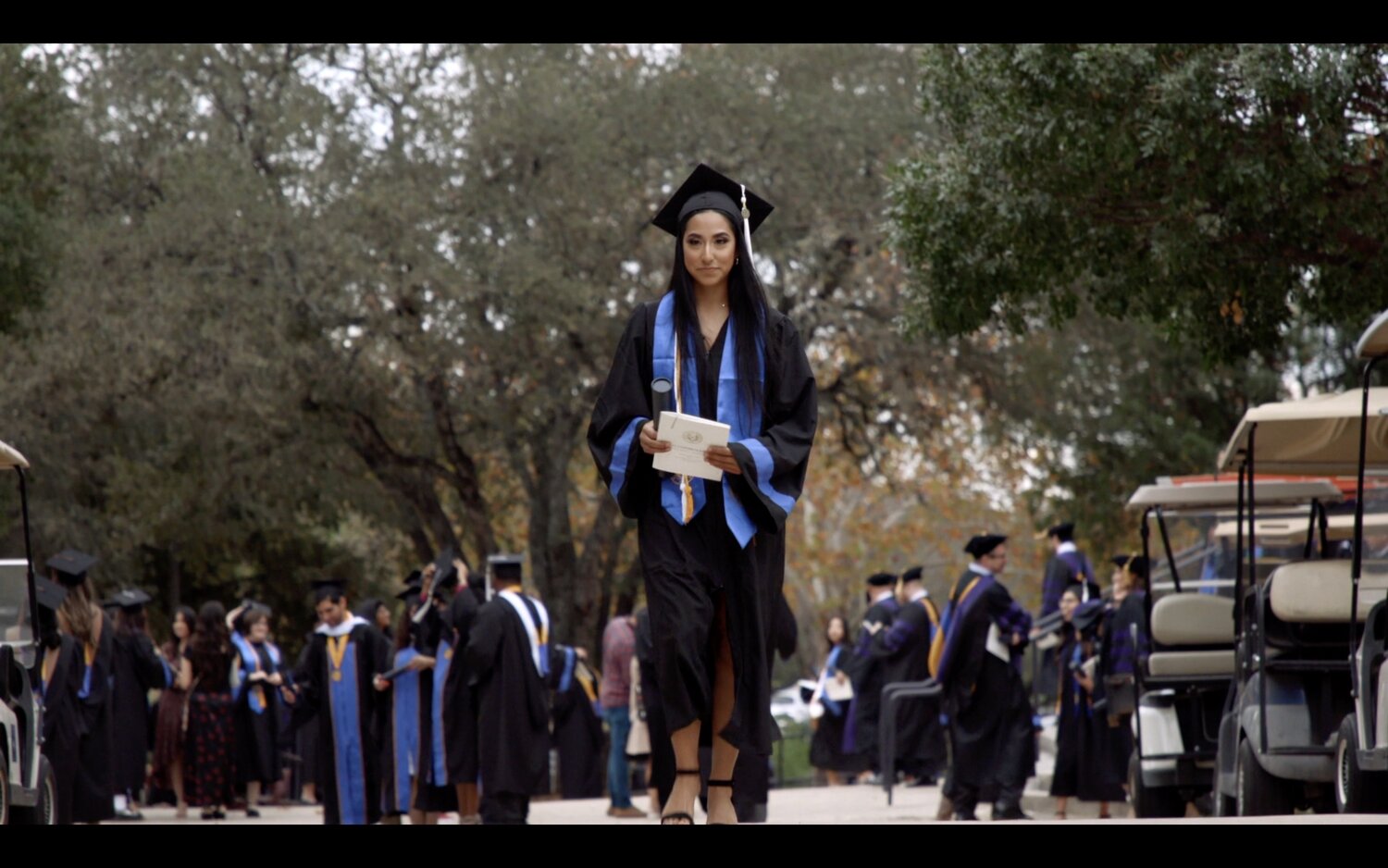

Concern for their own mental health likely wasn’t top-of-mind when the newsroom was in the thick of reporting on what happened at Robb Elementary that day. But over time, they had conversations about self-care and counseling. Some in the newsroom sought professional help; others worked through the trauma and grief in their own way. The film follows Kimberly Mata-Rubio and her husband, Felix Rubio, as they grieve, find ways to honor their daughter, become resolved advocates for assault weapons bans and as Kim walks the stage at her college graduation — with her husband and a painfully incomplete row of her children in the audience. We see her return to the newspaper in a new advertising role.

Near the end of the film, members of the newsroom attend the annual South Texas Press Association conference, where they receive several awards for their coverage. Garnett talks about how difficult it is to keep a local newspaper alive today and how, each year, there are fewer attendees at the event because of shuttered newspapers. Before the film wrapped, they reduced their frequency from daily to weekly.

They welcomed a new team member in July 2023, Report for America Corps Member Sofi Zeman, who covers crime and the school district. A South Texas Press Association grant enabled them to hire a paid intern.

When asked how ULN is doing this year, Garnett told E&P, “Our page count is down. We’re putting out about 24 pages a week. … It’s a struggle each month to make ends meet. We think the best way forward — and Report for America has helped us with this — is to solicit philanthropy. We’ve learned a lot about crowdfunding. We also applied to Press Forward for a grant, and we’re optimistic that could keep us going for another couple of years.”

Garnett spoke of how a newsroom isn’t just like a family — it is family.

“I’ve not had to reduce any staff,” he said. “I just don't want to do that. So, that will be my epitaph: ‘He didn’t reduce staff.’”

The “Print It Black” documentary is now streaming on Hulu.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She's reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Gretchen A. Peck is a contributing editor to Editor & Publisher. She's reported for E&P since 2010 and welcomes comments at gretchenapeck@gmail.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here