When Seattle Times Co. president Alan Fisco kicked off 2019 with an editorial reflection on the past year, he listed lessons the news organization had learned and how he planned to leverage those lessons in the New Year. Among those initiatives was a promise to provide better customer service to subscribers, including better, more reliable in-home delivery. Specifically, Fisco cited a shortage in carriers. It’s not an anecdotal case for the Seattle Times. In fact, other publishers are finding a shortage in carriers ultimately harms the newspaper brand.

Then, in late December, a malware attack hit the Los Angeles Times and Tribune Publishing papers across the country, delaying weekend deliveries and “(infecting) systems crucial to the news production and printing process”—representing an entirely new threat to news organizations and how they deliver papers.

Recruiting Challenges

Speaking with E&P, Fisco went into his editorial a little further.

“In the Seattle marketplace, we’re dealing with a minimum wage of $15 an hour that’s being phased in. That puts a strain on carrier compensation and profile levels,” he explained. “At the same time those things are happening, our volumes are declining, so the routes are less dense. A typical route has fewer customers, and when there fewer customs, there are less profits for the carriers. It’s a squeeze.”

Delivery is, admittedly, something that keeps Fisco up at night.

Alan Fisco

Alan Fisco

“I worry that the cost of delivery becomes so incredibly expensive that we’ve got to reexamine our frequency and how we’re delivering,” he said. “That’s a reality that we’re going to be facing, maybe sooner than some people think.”

Fisco isn’t sitting passively on his hands as all this happens though. The newspaper has changed its profit structure for distribution partners. It was an expensive endeavor, but one he believes will pay off.

The second countermeasure Fisco implemented is in route restructuring. The routes are longer, but that incentivizes carriers. That may sound like a simple fix, but that also presents a production challenge. Longer routes take more time, but customers still expect their newspaper at the doorstep before their first sip of morning brew. Customer satisfaction will not be sacrificed, Fisco vowed.

“I know other papers that are going to press earlier in order to design larger, longer routes, but they’re dealing with the same issue,” he said. “We’ve gone to press a little early, but nothing significant. I think that’s something that we’ll have to be looking at over the next year to 18 months—taking a real hard look at our close times in the newsroom.”

At the Bozeman Daily Chronicle in Montana, a lack of carriers has forced the office staff at the newspaper to “pitch in” to help with deliveries. The staff published a letter to the readers in October 2018 offering an explanation for the “down routes.”

“Approximately 20 percent of our readers and subscribers have no contracted carrier assigned to their delivery route,” it read.

As Fisco pointed out in his editorial, the need is pervasive among small, mid- and major-market titles. The Denver Post is advertising for carriers. The Cleveland Plain Dealer in Ohio is too. Even as the Washington Post spent millions on a Super Bowl commercial, the company continued to search for carriers to get its printed newspaper to paying customers.

“Recruitment—today more than ever—is the lifeblood of a successful home-delivery operation,” said Eduardo Delfin, vice president of circulation, customer service and administration for the Philadelphia Media Network (PMN). “Unfortunately, the past 18 to 24 months have been challenging beyond anything I have experienced in my 40 years in the circulation business.

Delfin oversees distribution for a 10-county metropolitan Philadelphia territory. The organization not only delivers its own titles—the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News—but also the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and several others.

Eduardo Delfin

Eduardo Delfin

To appeal to would-be carriers, PMN advertises in its own newspapers and in external local and regional publications.

“We use flyers, lawn signs, magnetic signs for vehicles, a robust social-media campaign and radio,” Delfin said. “And we have a community outreach program where we are in contact with job-placing agencies, churches, and any location that would add exposure to our recruitment efforts.”

To what does Delfin attribute the “carrier drought?”

“The reason for the problem is that we are competing with Amazon and UPS, and other warehouse jobs, along with Uber, Lyft, and in this area, a very strong WaWa (brand) of stores for those same folks looking for part-time jobs, and a low unemployment rate,” he said. “While we have invested in higher fees and additional support, through more field staff, including delivery assistants, the carrier turnover is high, which in turn hurts our ability to provide consistent, good delivery service to our subscribers. Additionally, we have started offering finder’s fees and retention bonuses to attract and keep those new carriers.”

How great of a challenge is this for Delfin and his professional peers around the nation? “I personally have been expending 25 to 50 percent of my week directly or indirectly on recruitment,” he said. “We feel that we need to continue what we are doing, even doing more of it, while exploring any new recruitment avenue. It is a challenge.”

The BH Media Group produces 31 daily newspapers, 47 weekly newspapers and various other print and digital publications. As vice president of audience growth and distribution, Lance “Gayle” Pryor knows all too well the bane of a carrier shortage, but to him, it’s not a new phenomenon.

“It always happens when the economy is growing,” he said.

He also pointed out that the nature of the job isn’t new either. The gig is inherently part-time in nature, and carrier candidates have typically sought out the work because they’ve wanted a part-time commitment and a supplemental source of income.

Lance “Gayle” Pryor

Lance “Gayle” Pryor

Decades ago, that ideal candidate may have looked a little different. The “paper route kid” is practically the stuff of sentimental lore now; today, he’s grown up and retired.

Pryor recalled reading a news article a few years back, which cited a statistic that stayed with him—thousands of Baby Boomers retire each day, and the vast majority of them cannot afford to retire without some supplemental income coming in.

“Most (Baby Boomers) grew up with newspapers, believe in newspapers and many have business backgrounds,” he said. “It’s a no brainer.”

Pryor said that BH Media Group is reaching out and targeting retirees and retired veterans. The company’s circulation directors have been dispatched to local retirement and veteran organizations to spread the word: If you need and want part-time work, we’ve got a job for you.

One of their newspapers ran ads in 20 local church bulletins. Local community Facebook pages are also good places appeal to likely carrier candidates.

Overcoming the carrier challenge is just one aspect of customer service, Pryor noted.

“First, their delivery…is it on time, in a dry, readable condition? Is it where they’re looking for it every day? And then, if there is an issue and they do need to call us, how do we handle it? Are we effectively dealing with our customers?” he said.

Though we’re cognizant of it within industry circles, newspapers haven’t done a great job of broadcasting how remarkable it is that we do what we do every day, Pryor said: “We create something new and different, 365 days a year, and deliver it to you in person. Nobody else does that.”

Removing an Infection

The first sign of trouble was a server outage at the production and printing facility that produced the Los Angeles Times, the San Diego Union-Tribune, and other major-market titles. To wrap some context around the crime: More than 3.7 million newspapers are produced at the plant in an average week. Per the Times’ 2018 count, the facility prints an estimated 195 million newspapers each year.

Last December, the Times reported on what proved to be a “malware attack, which appears to have originated from outside the United States.” Tribune Publishing stated that no personal data about subscriber nor advertisers had been compromised or stolen.

The report said: “The attack delayed distribution of Saturday editions of the Los Angeles Times and San Diego Union Tribune. It also stymied distribution of the West Coast editions of the Wall Street Journal and New York Times, which are printed at the Los Angeles Times’ Olympic printing plant in downtown Los Angeles.”

In the end, Tribune disclosed that it had isolated the attack to “Ryuk ransomware.” Attempts to reach the Times and Tribune for further comment were unsuccessful.

At the Seattle Times, Fisco followed the news out of Los Angeles closely. His company has developed an IT team with several members who are particularly skilled in warding off cyberthreats.

“We’ve made some modifications,” Fisco said. “We’ve had a couple of attempted hacks, and that’s becoming fairly routine, fairly common unfortunately. We’ve gone so far as to block some IP addresses from certain geographies of the world, where we know we’re not doing business, and yet still get these ‘intrusions’ coming from other counties…We also adhere to all the standards to make sure that we’re protecting customer credit card information and their privacy.”

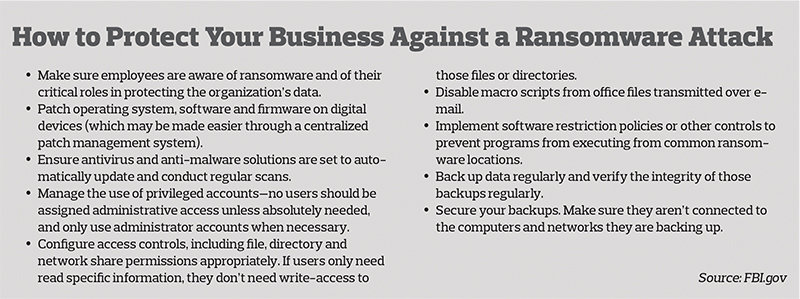

In its most simplistic form, ransomware may infect network systems and literally prompt the victim to “pay up” to get back in. But how broad and real is the cyberthreat to U.S. news organizations, and what should publishers know about this new strain of ransomware?

Richard Stiennon, founder of IT-Harvest, an analyst and consultancy firm, and an expert on cybersecurity explained how Ryuk was likely introduced to the network: By opening a nefarious email attachment or by clicking on an internet link, which is the more common method of infection today. It may also be spread by a “botnet,” which Norton Antivirus refers to as “the workhorses of the internet.” They can be both legal and productive—driving repetitive tasks that keeps networks and websites working—or they can be malicious and decidedly illegal.

Richard Stiennon

Richard Stiennon

“In order to take out a whole operation, it’s got some ability to spread internally over the network,” Stiennon said. “It’s ransomware and acts like ransomware that encrypts the hard drive, but then it immediately destroys the encryption key. There’s no intent to get a ransom; it’s just purely destructive.”

In the world of cybersecurity, there are known “targets of opportunity,” Stiennon said. Manufacturing is one, and it doesn’t matter to criminal foreign agents whether it’s a printing plant producing newspapers or one that turns out automobiles. Bad actors from Russia, Iran and North Korea may seize upon any vulnerability they can find.

There is speculation that Ryuk may have originated in North Korea, based on its similarities to the HERMES ransomware know to come out the authoritarian nation.

“The Lazarus Group, which is North Korea—that’s who Check Point attributes this to,” Stiennon said, referencing the software developer and cybersecurity research firm. “This would be a way for them to rattle their sabers and demonstrate their prowess. The thing about these operators is that they work in a dictatorial environment, so there’s probably a lot of whip-cracking over them to produce results. And from their perspective, what a great result. ‘Look at this! We can take down these printing plants!’”

Cybersecurity contributor Davey Winder wrote about the incident in Forbes, and offered some context about the Lazarus Group: “The trademark of this group is to undertake highly targeted and well-researched and resourced attacks involving the kind of reconnaissance usually associated with state-sponsored threat actors. Perhaps the best known example of the work of the Lazarus Group is the 2014 breach at Sony Pictures.”

Tribune wasn’t the only target for this breed of malware. Two months before the attack, the Onslow Water and Sewer Authority (OWASA) in North Carolina had its own systems disrupted by Ryuk malware. Though the water company reported that it had no interruption in services, the organization’s security systems had to essentially be rebuilt.

What makes publishing and printing operations particularly vulnerable to malware attack is that the workflow is so integrated. Content originators are digitally connected to art, production, prepress systems and more. The business side of the organization is typically well integrated, too. The seamless digital workflow that publishers have aspired to be may, in fact, be news publishing’s greatest cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

Stiennon suggested that re-engineering workflow to inject some “air gaps” in the workflow may decrease the risk. He is empathetic to publishers who may be resistant to that idea, because air gaps typically inject more time—and thus, cost—to the workflow. But he implores news organizations to consider the broader threat, that the Tribune attack was “a demonstration of what’s possible.”

The good news for publishers is that investing in cybersecurity will cost them a fraction of what it would have cost 10 to 15 years ago, Stiennon said. If any organization is using Microsoft Windows in any capacity, Stiennon suggested they upgrade to Windows 10.

“Most publishers have survived by going to the web and taking advantage of new technology, not to mention their digital offset printers and all the technology they’ve employed, and they’ve done that without consequences of doing it securely,” he said.

Gretchen A. Peck is an independent journalist who has reported on publishing and printing for more than two decades. She has contributed to Editor & Publisher since 2010 and can be reached at gretchenapeck@gmail.com or gretchenapeck.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here