For many of their users, mobile messaging apps are just expedient little tools for texting and sharing photos or videos with friends who use the same app. The fact that those messages and content are encrypted is just an added a perk. But for journalists and their sources—especially sensitive sources like whistleblowers—encrypted messaging apps are an increasingly valuable means of communication, which provide a modicum of assurance that the information being exchanged is private and protected from anyone outside of that conversational relationship.

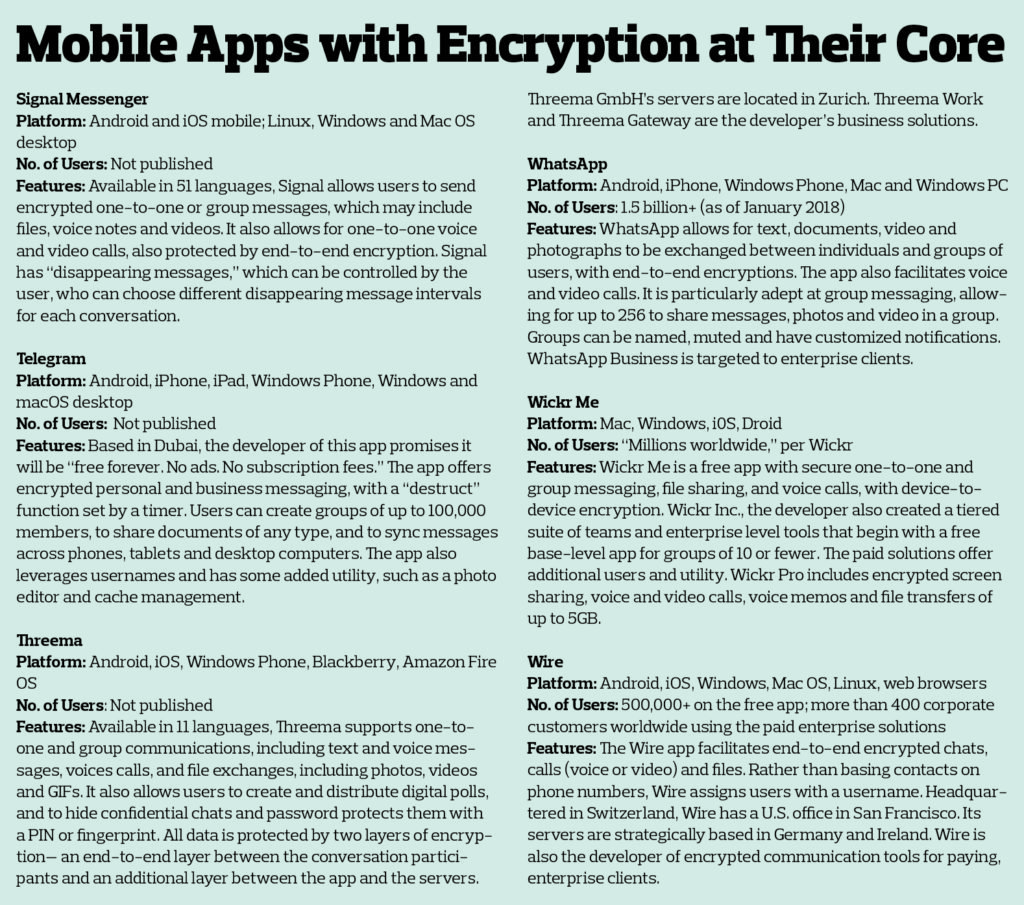

In the encrypted mobile messaging space, there are both major and minor players. Some are lesser known brands, like Threema, a Swiss-developed suite of mobile apps that encrypt text messages, documents, and voice calls for both Droid and AppleOS devices. The developer promises users, who pay for this app, “seriously secure messaging.”

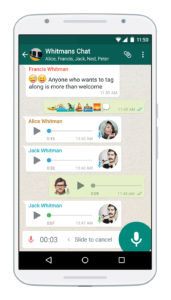

Others are wildly popular—ubiquitous even—in some markets. Take Facebook-owned WhatsApp, for example, which at last count (January 2018) boasts more than 1.5 billion users worldwide.

Journalists have been quick adopters of Signal, a messaging app tied only to the users’ mobile number, allowing anyone with the app and that number to reach out to reporters in confidence.

Morten Brøgger

Morten Brøgger

Wire, which had a large European following initially, has gained some traction in North America and around the world. Morten Brøgger, Wire’s CEO, estimated that Wire now has a half-million users of its free encryption app and more than 400 paying enterprise clients.

Wire is different than other tools not just in business model, but in the way that it’s been designed. In terms of the business model, the developer courted those enterprise clients by addressing corporations’ needs to communicate securely and privately.

Email is very “last millennium” the CEO suggested and said that Wire’s design is “the new black.” First, the Wire interface is designed to be consumer friendly and “very modern.” But it’s not just how it looks that’s distinctive; it’s how Wire implements encryption that’s significant, too.

“In the classic cloud, you have the application in the cloud, and all the users with their devices are connected to that,” Brøgger explained. “In the cloud, you have all the logic, all the processing, all the storage, all the security, and if that traditional SaaS provider offers encryption, the encryption keys will be stored centrally in the cloud.”

The problem with this model is that it creates a vulnerability he calls “the man in the middle.” If hackers can compromise the cloud, they can get access to the encryption keys, making it possible to decipher the content.

Wire’s solution is more like a “distributed cloud,” he said. “Some of the logic is in the middle, but a lot of the logic is actually on the client. We have some of the processing, but not all of it. We have some of the storage, but not all of it…So we have none of the encrypted content.”

Brøgger said that Wire’s philosophy is that people have a human right to communicate privately, especially in the cases of journalists and sources or enterprise clients protecting intellectual property and business communications.

The Wire app is based on a distributed cloud architecture, which minimizes vulnerabilities, such as cyber threats and hacking. It also means that the developer never fully possesses the encrypted content.

The Wire app is based on a distributed cloud architecture, which minimizes vulnerabilities, such as cyber threats and hacking. It also means that the developer never fully possesses the encrypted content.

Communicating in Confidence

Because they’re free or low cost and readily available for download, journalists often leverage multiple messaging apps, giving sources the opportunity to communicate in however they feel most comfortable.

BuzzFeed News’ cybersecurity correspondent Kevin Collier uses several encryption tools for communication. Choosing which to use largely has to do with a source’s preference.

“Signal is the one I use most frequently,” he said. “If I have a source who requests Wire or Wickr, I will…Sometimes, it’ll be a hacker or a security-type of source who is partial to one of those. If it’s someone who is well informed in this space, I’ll acquiesce to them. Overwhelmingly, though, I’ll use Signal, and if it’s a source who doesn’t seem particularly up on the issue, I’ll request that we use Signal if it’s remotely sensitive.”

Collier suggested that email is perhaps one of the most vulnerable means of communication, and cited some research he’d done about the hacking of email accounts to persons related to the “Gulf conflict” policy, including a Trump Administration advisor. Email is rightfully seen as problematic.

“There is a broad consensus that if you’re going to be speaking using technology that is readily available to most people, Signal and its disappearing messages—and I’ve really got to stress the disappearing messages part—is still your best bet,” Collier said. “That said, a truly dedicated adversary—by which I mean most governments—they can usually find a way in…If the U.S. government, with its full range of legal powers, truly wants your messages, there’s a pretty strong chance they will get them.”

Aaron Mehta first began using WhatsApp and Signal apps in 2017, largely because sources asked to communicate in this way. Mehta has a highly sensitive and sometimes secretive beat as the deputy editor and senior Pentagon correspondent at Defense News, which covers the global defense community.

When asked if WhatsApp and Signal have played a significant role in his communications with sensitive sources or whistleblowers, Mehta said, “Absolutely.”

“I think a lot of journalists last year woke up to the necessity of using them,” he added.

It’s not just sources who come to him and ask to communicate in this way. He sees it as part of his due diligence to suggest these apps as a preferred means of digital communications.

“Part of our job as journalists is to protect sources from themselves sometimes,” Mehta said.

Should governments around the world wage a successful campaign against encryption, Mehta suggests that it would present a challenge because these technologies are so easy to use and readily available; however, he believes journalists and sources will learn to adapt.

Devlin Barrett

Devlin Barrett

As a reporter covering national security and law enforcement at the Washington Post, Devlin Barrett has some special experience with encrypted apps.

“I think they’re useful tools, but I don’t think they’re a magic bullet when it comes to secure communications,” he said. “When it comes to source protection, human behavior, to me, is just as important as the mechanical means of communication.”

During his years in journalism, Barrett observed what he calls a “continuum”—a natural evolution—of digital communications. Encrypted mobile apps did not just spring forth from a vacuum.

“People are really into encrypted apps post-Snowden and in the heightened investigation space that we’re now in,” he said. “There was a time when sources wanted to talk on AIM (AOL Instant Messenger) because that was more secure for them than just calling on the phone. Then, people wanted to talk on Facebook, because they thought that was more secure. People wanted to text. And now, you have encrypted messaging apps. There’s an arc to this.”

Barrett also observed that it’s been the habit with digital communication technologies that developers will amass a user base that’s fully confident in privacy and security, only to see it compromised “in the long run.”

“My concern as a reporter is that there is always going to be someone trying to look over your shoulder at your conversation, and you want to make sure that doesn’t happen,” he said. “You have to be very careful and put a lot of thought into how you operate.”

When Security is Attacked

Encryption is, in theory, a secure means of communication, but these mobile apps have not been without vulnerabilities. In Zurich last year, German cryptographers from Ruhr University spoke before an audience at the Real World Crypto Security Conference, revealing that they’d discovered a breach in WhatsApp, which allowed hackers to infiltrate group chat communications on the platform.

In 2017, the British government reportedly asked WhatsApp developers to create a “backdoor” entry to the mobile app, which would essentially allow law enforcement to obtain the content of encrypted communications in the case of battling crime and thwarting terrorism. They cited the case of Khalid Masood, the terrorist who drove a car into a crowd of people outside the Palace of Westminster, who was believed to have used WhatsApp just two minutes prior the attack, implying the app may have been instrumental to his plan or that it could’ve been thwarted had authorities been able to intercept his messages.

The request was rejected, and when Sky News reported on it, WhatsApp responded in a statement, “We carefully review, validate, and respond to law enforcement requests based on applicable law and policy, and we prioritize responses to emergency requests.”

When terrorists killed 14 people and injured 22 others in San Bernardino, Calif. in 2015, Apple received a similar request from the U.S. Federal Government, which sought a “backdoor” in order to access encrypted content on the suspects’ iPhones. Apple resisted in court, but eventually, the Feds reported that it had found a way to access data on those phones without Apple’s help.

“Over time, law enforcement gets smarter and comes up with a work-around to things that flummox them,” Barrett said. “The long-term effects of the Snowden case is that the tech companies decided that they would publicly oppose government efforts to—in their terms—make a sort of large, meaningful, accessible backdoor for government and law enforcement to go in with a court order and get the information they want access to.

“Sometimes that means that all they know is that someone exchanged a lot of encrypted messages with another person at a specific time, but you still don’t know the actual content of the messages. One of the things a lot of people don’t think ahead about is that when it comes to encrypted messaging, if law enforcement has access to the phone, the device itself doesn’t matter if the messages are encrypted or not. They just open the phone and read the whole thing…There may be an excess of confidence about the security of some of these (apps).”

Encrypted mobile devices were at the heart of the “Phantom Secure” bust, which compelled Vincent Ramos, the CEO of Phantom Secure, to enter a guilty plea in October 2018 to prosecutors in Southern California. Ramos and his co-conspirators had been using encrypted mobile devices to traffic cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine across North America and in Australia, Thailand and Europe.

In 2015, the Brazilian government was mounting a case against a drug trafficking ring and sought the help of WhatsApp to obtain the criminal enterprises’ encrypted messages. Facebook declined, and in retaliation, the mobile app was banned across the country, and a local Facebook executive was arrested. The punishment was short-lived when a day later, a judge overturned the ban and dismissed the obstruction allegations.

At the end of 2017, Reuters reported that the Australian parliament passed a law mandating that “backdoor” access to encrypted platforms. Other nations, such China and Russia, have outlawed end-to-end encryption apps entirely.

Here in the U.S., encryption has long been considered a challenge, if not a bane. Speaking in London at the 2017 Global Cyber Security Summit, Deputy Attorney General Rod J. Rosenstein said the Department of Justice coined a term, “responsible encryption.”

“We use (it) to describe platforms that allow police to access data when a judge determines that compelling law enforcement concerns outweigh the privacy interests of a particular user,” Rosenstein told summit attendees. “In contrast, warrant-proof encryption places zero value on law enforcement. Evidence remains unavailable to the police, no matter how great the harm to victims.”

In the Court of Public Opinion, it’s not hard to imagine this justification gaining traction with politicians and constituents and in spite of loss of privacy. It is fairly easy for politicians to convince the American people that freedoms should be sacrificed in the interest of safety.

“Warrant-proof encryption comes at a cost because it enables criminals and terrorists to communicate without fear of detection,” said Rosenstein. “Obviously, there is no Constitutional Right to sell warrant-proof encryption. If society chooses to let companies market technologies that cloak evidence of crimes, it should be a fully informed decision.”

Rosenstein isn’t the only government official encouraging the public to be better informed about the risk-benefit analysis of encrypted communications. In May 2015, then-FBI Director James Comey spoke at the American Law Institute and the Georgetown Law Center, where he cited encryption as being integral to international terrorist organization’s recruitment efforts and warned about criminals being able to “go dark,” the sinister term adopted by U.S. Federal agencies.

Amy Hess, the FBI’s executive assistant director for the Science and Technology Branch, went to Congress in April 2015 to implore a Congressional Oversight Committee to consider how encryption has made it increasingly difficult for the Bureau to access both “data in motion” and “data at rest.” To the committee members, she said, “If there is no way to access encrypted systems and data, we may not be able to identify those who seek to steal our technology, our state secrets, our intellectual property and our trade secrets.”

Fear is a powerful motivator.

“I don’t think we’re likely to see a grand compromise (between the Feds and developers) anytime soon, but that’s certainly what law enforcement would like,” Barrett said. “I think there are parts of the technology world that would be willing to do that, but overall, the technology sector is not willing to have sort of a public, grand compromise with the government when it comes to encryption.”

The protection of encrypted technologies and communication has a somewhat unlikely ally—the U.S. government. A bipartisan group of U.S. Congressional Representatives, led by Ted Lieu (D-CA), introduced a bill to the House last June (H.R. 6044—ENCRYPT Act of 2018) which seeks to protect the privacy of citizens using these tools and prevent state and federal government agencies from mandating by law that developers turn over their encryption coding.

Target-Rich Opportunity

With more than 1.5 billion users worldwide, Facebook’s WhatsApp is perhaps the most widely recognized and downloaded mobile app that offers end-to-end encryption.

With more than 1.5 billion users worldwide, Facebook’s WhatsApp is perhaps the most widely recognized and downloaded mobile app that offers end-to-end encryption.

There’s another way in which encrypted mobile technologies are being threatened: developers chasing revenue. The popular WhatsApp has amassed a formidable, tech-friendly audience that advertisers and marketers want to woo. Up to this point, WhatsApp has remained ad free, and that’s largely because of the fundamental encryption technology. It means that servers on WhatsApp only have access to the users’ phone number, never any of the raw data or content. To intelligently target digital mobile ads, marketers fundamentally require, at bare minimum, data related to keywords.

But marketers can be a persistent bunch, and they’re like dangling carrots before app developers.

E&P asked Wire’s Brøgger if the company had any plans to “monetize” its community. “No,” he said. “That is exactly why Wire has pivoted to focusing on monetizing our applications—not our users—by selling to enterprises, which also benefit from reducing the risk of malware.”

He also added that he feels confident that other encrypted messaging apps may go down that path, chasing after data-driven revenue and potentially compromising the safety nets encryption affords.

Developers may feel users in Europe push back harder against the monetization of audiences, in comparison to users here in the States. Barrett noted that the conversations about privacy are distinctive. In the U.S., the greatest perceived threat to privacy is the government, while in Europe, privacy debates are largely focused on corporate intrusion and malfeasance.

In addition, developers will likely continue to feel the pressure to both deliver a secure, reliable experience to their app users and to be supportive when law enforcement and a court order comes calling.

As Congress considers the risk-benefit analysis of encrypted mobile apps—weighing issues like privacy, cybersecurity, whistleblowers and counter-terrorism—encrypted mobile apps will remain the best digital option for communications between sources and reporters.

Or, as Mehta suggests, “Meeting in person or over the phone is the best way to make sure there’s no trace on you.”

Gretchen A. Peck is an independent journalist who has reported on publishing and printing for more than two decades. She has contributed to Editor & Publisher since 2010 and can be reached at gretchenapeck@gmail.com or gretchenapeck.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here